Correlation#

Important Readings

[FPP07], Chapters 8 and 9

Scatter Plots#

The relationship between two quantitative variables can be explored in a scatter plot. You need data that is paired, like in the father and son data below. Each \(x,y\) pair is plotted and you might notice a trend from the shape of the scatter of points.

Father’s Height (inches) |

Son’s Height (inches) |

|---|---|

65.0 |

59.8 |

63.3 |

63.2 |

65.0 |

63.3 |

The relationship is called an association. When the scatter of points slopes upward, that shows a positive association. If the scatter slopes downward, that shows a negative association. A strong association indicates that one variable can be used to predict the others.

Fig. 22 There is a positive association between a father’s height and his son’s height. The orange points are for the three pairs shown in the table above.#

The variable on the \(x\)-axis is thought of as the independent variable and the \(y\)-axis variable is the dependent variable. This language suggests that the \(x\) variable is the one influencing the \(y\), suggesting (1) \(y\) is predicted from \(x\) or (2) there’s a direction of causality being hypothesized. In this class, we have learned to be cautious in claiming causality. Go ahead and choose one variable as the independent variable and the other as the dependent without too much angst or hesitation. Just be ready to be humbled if you ultimately find the there is no causal relationship or if you get the direction backwards.

For each of these two pairs, which variable would you choose as the independent variable?

Hours of sleep and test performance on the following day

Public assistance (like welfare) and poverty

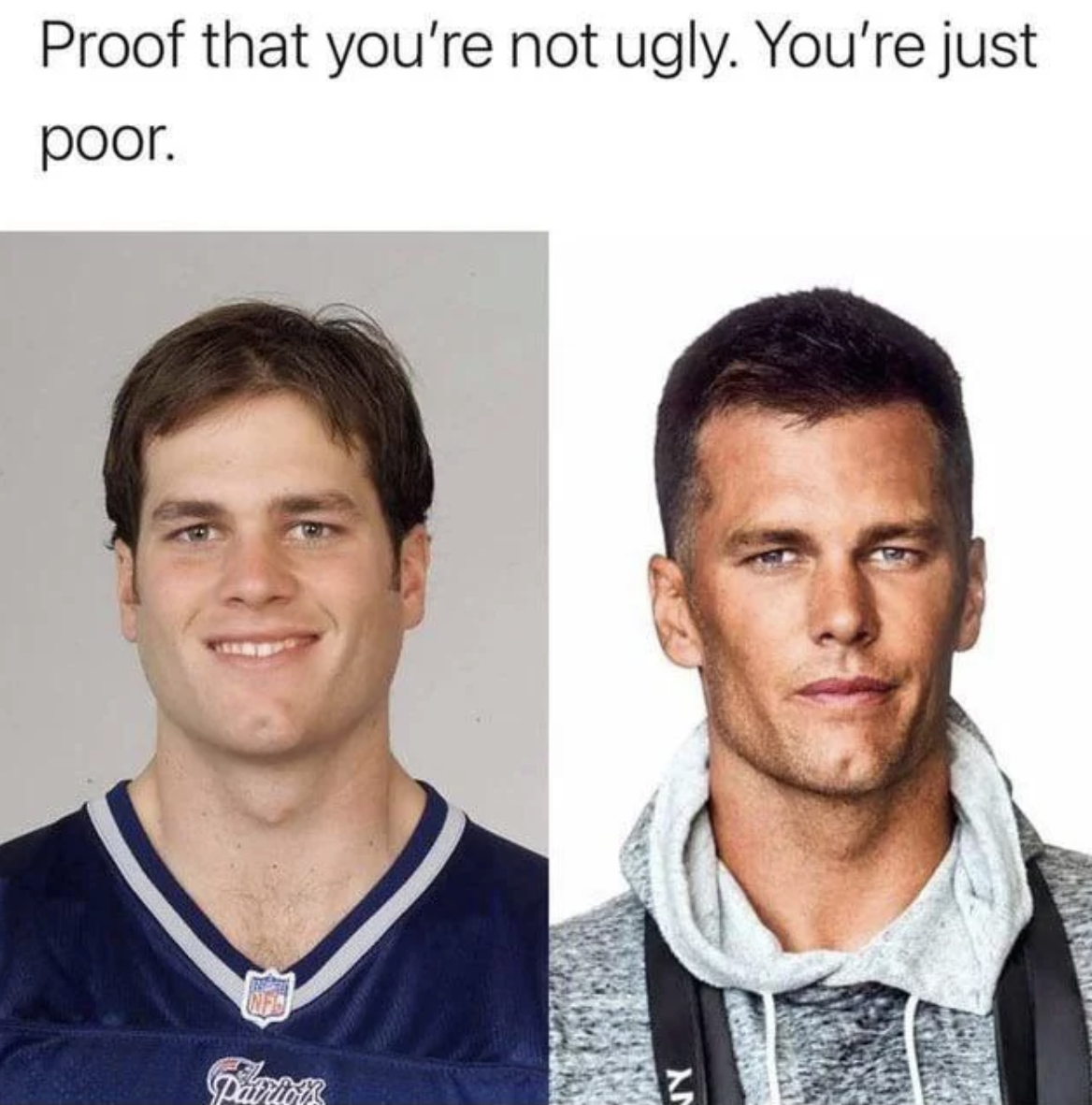

Attractiveness and income

Sleep and test performance

Sleep should be the independent variable, especially given the temporal precedence.

Public assistance and poverty

Either choice is justified. First, let’s consider public assistance as the independent variable. You don’t have to be taking a stance on there being a positive or negative relationship. Statistician Udny Yule considered spending on public assistance as the independent variable and poverty as the dependent variable in his “investigation into the causes of changes in pauperism in England,” finding a positive relationship ([Yul99]). This is the association you would expect if you believe that assistance promotes dependency and increases poverty. Public assistance might also break cycles of poverty, leading to a negative relationship. This can still be compatible with Yule’s data if you recognize that it’s important to consider the other direction.

Societies that experience more poverty might spend more on public assistance. Given that spending responds to poverty levels, it can also be appropriate to consider poverty as the independent variable.

Attractiveness and income

Either choice is justified. [MJEL21] considers attractiveness as the independent variable and earnings as the dependent variable in examining the “returns to physical attractiveness.” However, as the figure below suggests, the effect can go both ways.

Correlation Coefficient#

The correlation coefficient, denoted \(r\), is a units-free measure of linear association, or clustering around a line. The coefficient falls between -1 and 1. It doesn’t matter which of the two variables is thought of as the independent or dependent variable. The correlation coefficient shouldn’t be confused with the slope of a trend line-it’s more about the tightness of the scatter around some line. The correlation will be one if \(x\) and \(y\) are perfectly linearly related with a slope of 0.2 or a slope of 200. A correlation coefficient of 1 or -1 means that one of the two variables will perfectly predict the other in the data. More moderate correlation coefficients indicate a less predictive relationship.

Fig. 23 The trend line on the left has a greater slope but the correlation coefficient is lower because \(y\) is less predictable given \(x\).#

Interactives#

You can drag around the data points and delete individual points in the plot below to see how the correlation coefficient responds. Notice some limitations:

A correlation coefficient of 0.8 doesn’t indicate an association twice as strong as a correlation of 0.4 in any natural sense.

A correlaton coefficient of 0.8 doesn’t mean 80% of the points fall on a trend line. For now, we don’t say anything much deeper than 0.8 represents a stronger linear association than 0.4.

Below, you can adjust a random noise parameter and a slope parameter and observe how the correlation coefficient changes. The \(y\)-value is calculated as \(\text{slope} \times (x + \text{noise})\).

Notice a few things.

Increasing the noise will decrease the predictability of \(y\) from \(x\) (and \(x\) from \(y\)). The correlation coefficient will tend to decrease.

Changing the slope doesn’t change the correlation coefficient unless we flip the sign of the relationship. This underscores that correlation is about the clustering around a line and not the effect size indicated by the slope.

Calculation#

The coefficient, \(r\), is calculated as the average of the products of the standardized values,

The product of two standardized values is positive if the data moves together. If \(x\) is above its average when \(y\) is above its average, this will increase the correlation. If the two variables move in opposite directions, \(x\) goes up when \(y\) goes down, then this decreases the correlation coefficient.

Fig. 24 Points in the positive quadrants, where both \(x\) and \(y\) are above or below the average, push the correlation coefficient up. The data on the left is negatively correlated. The data on the right is positively correlated.#

Example#

Consider the eight \(x\)-\(y\) pairs in the table below.

First, we must standardize the values. In this case, the data is already standardized because the average is zero and the SD is one.

Then, the correlation coefficient is calculated by averaging the product of the paired standardized values,

What if we considered the alternate data set below?

\(x^{\prime}\)

Now, \(\text{SD}_x\) is 2 and \(\text{SD}_y\) is unchanged.

Exceptional Cases#

Per [FPP07], the corrrelation coefficient is useful for “football-shaped scatter diagrams.”

Fig. 25 A football-shaped football.#

This is meant to rule out anything obviously non-linear. A surprisingly precise football shape arises when \(x\) and \(y\) both follow a normal curve like in Fig. 26.

Fig. 26 A football-shaped scatter diagram. The football shape arises from the bell-shaped distributions for both variables. The tapering comes from there being fewer values at the extreme \(x\) and \(y\) values.#

Anscombe’s Quartet is a set of four data sets that demonstrate the limitations of a correlation coefficient.

The top right panel shows an obvious pattern, and one stronger than the pattern in the top left, but the correlation coefficient rates the association at 0.82 in either case. This is because the correlation coefficient only measures the linear association.

Causation#

The phrase “correlation does not imply causation” is often uttered in recognition that a correlation between two variables doesn’t mean one causes the other. Correlation only quantifies if there is a predictable linear relationship between two variables.

When two variables are highly correlated without their being a causal relationship, that is often called a spurious correlation. Spurious correlation arise in observational data when there is a confounding third variable. Michael Luca gives a few examples of misinterpreted correlations in his Harvard Business Review article, Leaders: Stop Confusing Correlation with Causation.

One of Luca’s examples is a classic case of spurious correlation.

[Economists at eBay] analyzed natural experiments and conducted a new randomized controlled trial, and found that these ads were largely a waste, despite what the marketing team previously believed. The advertisements were targeting people who were already likely to shop on eBay. The targeted customers’ pre-existing purchase intentions were responsible for both the advertisements being shown and the purchase decisions. eBay’s marketing team made the mistake of underappreciating this factor, and instead assuming that the observed correlation was a result of advertisements causing purchases.

Fig. 27 Ads don’t lead to higher sales if the people who receive targeted ads were targeted for their interest in the product and would have spent more regardless.#

So, we know that correlation does not imply causation. Less appreciated sometimes is that no correlation need not imply no causation. Luca gives the example of police spending and crime, highlighting a chicken and egg problem in any observational study.

A 2020 Washington Post article examined the correlation between police spending and crime. It concluded that, “A review of spending on state and local police over the past 60 years … shows no correlation nationally between spending and crime rates.” This correlation is misleading. An important driver of police spending is the current level of crime, which creates a chicken and egg scenario. Causal research has, in fact, shown that more police lead to a reduction in crime.

For a similar example, consider the relationship between public assistance and poverty studied by Yule in the 1800s. Yule found a positive correlation between poverty and public assistance. A naive read of the data might suggest that increasing public assistance will cause poverty to go up, but there’s nothing in the correlation by itself that should suggest this because of the same chicken and egg problem.

Fig. 28 A positive, negative, or zero correlation can be misleading in either case.#

Exercises#

Exercise 22

A movie theater clerk wants to know the correlation between daily ticket sales for Matt Damon and Mark Wahlberg movies. He records the following data over three days. Find the correlation.

Day of Week |

Matt Damon |

Mark Wahlberg |

|---|---|---|

Monday |

0 |

3 |

Tuesday |

0 |

0 |

Wednesday |

6 |

3 |

The clerk finds he mixed up Matt Damon and Wahlberg. This is the actual data, below. Does the correlation change?

Day of Week |

Mark Wahlberg |

Matt Damon |

|---|---|---|

Monday |

0 |

3 |

Tuesday |

0 |

0 |

Wednesday |

6 |

3 |

Oops! The clerk messed up again. It turns out he initially corrected his error on Wednesday, so this is the actual data. Does the correlation coefficient change?

Day of Week |

Mark Wahlberg |

Matt Damon |

|---|---|---|

Monday |

0 |

3 |

Tuesday |

0 |

0 |

Wednesday |

3 |

6 |

Exercise 23

A journalist is investigating bloat in colleges hiring more and more non-faculty employees. In particular, the journalist focuses on mental health professionals. They study many campuses and find no correlation between money spent on mental health and a trusted measure of mental health. The journalist writes an article accusing schools of wasting money and receives an award for data-driven journalism. Is the award merited? Why or why not?